Archive

FNQB: Brady, Eli and the top 25 QBs of All-Time

This Super Bowl 46 edition of Friday Night Quarterback focuses on the Hall of Fame standard for quarterbacks. There are 25 quarterbacks in the Hall of Fame. I made an off-handed remark the other day that Eli Manning is certainly going to end his career as one of the 25 greatest quarterbacks of all time if only because there are fewer all-time great quarterbacks than it seems like. When I have done some deeper digging, that may not be entirely accurate.

Eli Manning is certainly a better quarterback than some who are in the Hall of Fame already, but to be one of the 25 best ever to play the game, Eli might need to rank better than some of his peers in the modern game. Ben Roethlisberger is not going to retire as one of the 25 best ever to play. There’s an argument to be made for Eli over Big Ben, but not such a convincing one that Eli Manning can easily be placed among the top 25 QBs of all time, while Roethlisberger is given no chance to someday make that list.

Quickly now, I want to sort out the already Hall-of-Famers to determine the quickest path into the brotherhood of hall of fame passers:

The Group of Peyton Manning/Tom Brady comparables is as follows: Otto Graham, Sammy Baugh, Dan Marino, Johnny Unitas, Joe Montana. It seems for certain that at the end of their careers, Peyton Manning and Tom Brady will make this a list of seven (maybe eight, when Drew Brees is done) of the greatest passers of all time.

The top half Hall-of-Famers is a group that really isn’t realistically in the conversation of “greatest to ever play”, but clearly is a step above the rest. Dan Fouts and Steve Young are right at the top: they could go in the next group up if they had any case — beyond the outdated passer rating statistic — of being the G.O.A.T. Then after that, Norm Van Brocklin and John Elway come up, along with Sonny Jurgensen, Sid Luckman, Roger Staubach, and Fran Tarkenton. Finally, I’ll put Len Dawson here because he doesn’t fit neatly into any classification with other Hall of Fame quarterbacks. Brett Favre, when he is finally eligible, belongs in this group. Philip Rivers will likely someday belong with this group as well. To make a case for a non-active player in the Hall of Fame, they really have to be able to neatly fit in this group to be considered a true “oversight.” Kenny Anderson is close to this group, but hasn’t been able to get in.

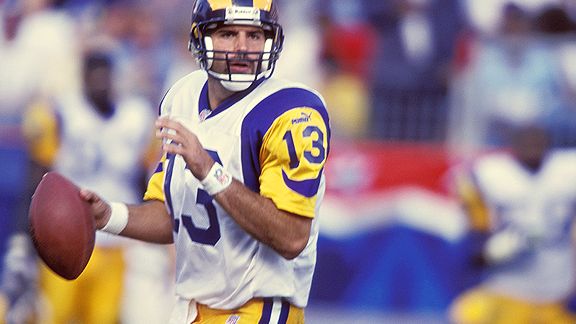

The legacy picks might be the easiest way for a guy like Big Ben Roethlisberger or Eli Manning to get into the Hall of Fame: win multiple super bowls. It worked for Terry Bradshaw and for Troy Aikman, who headline this group, though Jim Plunkett is still waiting on his hall-call. Joe Namath belongs in this group. Bart Starr belongs here. Y.A. Tittle was good at football for a very long time, and should get the nod here. And Bob Griese definitely belongs with this group, though he might have been the best quarterback of the four. Bob Waterfield belongs here because of the era he played in: he was no better a quarterback than Daryle Lamonica was 20 years later, but helped revolutionize the position. The fifth and final member of the legacy picks class is Warren Moon, the most recent inductee of the group. Warren’s statistical totals at the end of his career were largely unmatched, as is Warren Moon, nine-time pro bowler. Moon’s rate stats though say “consistently above average for the better part of 20 years.” I don’t see how that is any different from Namath though. This is the group where Donovan McNabb or Kurt Warner has their best case for the Hall of Fame.

Timing picks: Bobby Layne and Jim Kelly strike me as two guys who made it into the Pro Football Hall of Fame because of fortunate timing. Both were excellent players in their time, and multiple time pro bowlers, but I think if they had come eligible in other years, they easily could have been subjected to more of a debate, and then who knows what would have happened to their cases. Kelly went in on the first ballot. Len Dawson was on the ballot for seven years before he got in. Then there is the case of George Blanda, who is by far the least qualified quarterback in the Hall of Fame. If he had come eligible this year, he’s not even a finalist.

So the breakdown of 25 HoF quartebacks is as such, according to me: 5 in the discussion for greatest ever, 9 in the “top-half”, 8 in perhaps more on their historical legacies than their statistical accomplishments or performance levels, and 3 who might not have been famous or accomplished enough to make it in in a present day vote. Not a perfectly normal distribution, but it is close.

And while Brady ranks first or second on anyone’s active QB list (for career value), Eli Manning doesn’t rank higher than fifth or sixth on most people’s lists of active players with Hall of Fame cases. In fact, there are people who — if he fails to win on Sunday — would put him behind guys with no legitimate case such as Donovan McNabb, Matt Hasselbeck, and Tony Romo. To make the Hall of Fame, Eli is going to have to separate from guys like Ben Roethlisberger, Matt Schaub, and maybe Aaron Rodgers, and spend the next three years along with Philip Rivers and Drew Brees and Brady as the game’s elite quarterbacks. If Eli can retire a top ten quarterback in some meaningful statistical categories, then two (or even one) super bowl titles is enough to give him a solid Hall of Fame case.

This post is more concerned with him as one of the 20 to 25 greatest quarterbacks ever. There are 18 quarterbacks, either active or recently retired, who would qualify as all-time greats, a distinction that separates quarterbacks from merely being Hall of Famers or many-time super bowl winners. John Elway and Brett Favre are considered by the authorities of this blog to be all-time greats. Terry Bradshaw and Troy Aikman are hall-of-fame greats, at least in part to the seasons they had that resulted in titles. There is a distinction to be made.

Eli Manning, Philip Rivers, Ben Roethlisberger, and Aaron Rodgers are clearly not yet all-time greats of the game the way Peyton Manning, Drew Brees, and Tom Brady already are. But can the be considered among the greatest 25 quarterbacks in the history of the NFL? That is a little bit hazier. Let’s continue this activity with a couple of blind resumes. In all cases, the comparison is between one of the group of four quarterbacks above, and someone from the list of Hall of Fame quarterbacks.

Parenthesis represent a figure relative to league average

Group 1

Player A 7 twenty TD seasons, 58.4% career completion percentage, 5.9 career adjusted net yards per attempt, 4.7% career sack rate, 2 years QB rating > 90, 4 years QB rating > 80

Player B 6 twenty TD seasons, 56.9% career completion percentage, 5.6 career adjusted net yards per attempt, 6.6% career sack rate, 2 years QB Rating> 90, 7 years QB rating > 80

Group 2

Player C 7 twenty TD seasons, 60.1% career completion percentage, 5.9 career adjusted net yards per attempt, 6.3% career sack rate, 2 years QB rating > 90, 8 years QB rating > 80

Player D 3 twenty TD seasons, 63.1% career completion percentage, 6.4 career adjusted net yards per attempt, 8.7% career sack rate, 6 years QB rating > 90, 7 years QB rating > 80

Group 3

Player F 4 twenty TD seasons, 65.4% career completion percentage, 7.6 career adjusted net yards per attempt, 7.0% career sack rate, 4 years QB rating > 90

Player G 3 twenty TD seasons, 57.0% career completion percentage, 5.7 career adjusted net yards per attempt, 9.6% career sack rate, 3 years QB rating > 90, 5 years QB rating > 80

Group 4

Player H 6 twenty TD seasons, 63.5% career completion percentage, 7.2 career adjusted net yards per attempt, 5.3% career sack rate, 4 seasons QB rating > 90, 6 seasons QB rating > 80

Player J 1 twenty TD season, 61.5% career completion percentage, 5.7 career adjusted net yards per attempt, 5.2% career sack rate, 2 seasons QB rating > 90, 8 seasons QB rating > 80

***answers below the jump*** Read more…

The Return of Friday Night QB: What T.J. Yates, Christian Ponder, Andy Dalton, and Tim Tebow prove about NFL team behavior

The NFL is already flush with young quarterbacks, and this is a trend that will continue through the next two drafts. I know that much for certain. What’s far less clear is exactly what role those young quarterbacks will have on the NFL playoff picture and the NFL postseason. It is certain that they will matter, just not to what degree.

Offensive coordinators in pro football have an entirely different job now than they did even five years ago. In a world where the ability to hold your position for three consecutive years is rare, it is more critical than ever before to avoid having dismal quarterback play. You can not select a quarterback in the first round, or even be part of an organization that selects a quarterback in the first round, without being held accountable for the quarterback’s performance in his developmental years.

Lets look at the state of two struggling franchises: the Jaguars are undergoing some pretty significant organizational changes right now because Blaine Gabbert has not been good as a rookie and the Jaguars have lost games in a year where they have undergone a fantastic defensive transformation back to the top of the league. The offensive coordinator of the Carolina Panthers on the other hand, Rob Chudzinski, is now on a short list of potential head coaching candidates for the upcoming season because of the work that he has done with Cam Newton. It would not at all surprise me to see Chudzinski running the show in quarterback rich places like Indianapolis or St. Louis next year.

The Panthers, you may have realized, have the same record as the Jaguars this year. But with two equally touted college quarterbacks, one franchise has turned their pick into a must-see rookie of the year candidate, and the other franchise appears to be just playing their pick for lack of a better option. As far as building an organization, the Jaguars have been as good if not better than the Panthers at building a foundation for the future. They have the defense, they think they have the quarterback, and many of the pieces are already in place, pending the next coach because the current staff is taking the fall for the losing. The Panthers staff has created a culture of optimism based around Cam Newton, and though the optimism is probably no better founded there than in Jacksonville, the Panthers’ coaches are going to get better gigs than the Jags coaches next year. Style points do matter in the NFL.

Style points are why Tim Tebow is regarded as lightly as he is around the league. It’s hard to actually make the case that Denver’s passing offense has been a total disaster since Tebow took over. The Broncos have 13 total offensive touchdowns in exactly 13 halves of football since Tim Tebow became the quarterback, and Tebow personally accounted for 11 of those 13 touchdowns. Tebow has fumbled 5 times and thrown just one interception. For Tebow to have numbers like that and still significantly limit the passing game, he would have to be doing a lot worse than 45.5% completion and 6.0 yards per attempt. Whether or not Tebow’s historically low interception rate and relatively low fumble rates are sustainable is a different topic, but his value to the Broncos is pretty obvious.

Tebow has fundamental issues caused I believe by a changed throwing motion that has really hurt his arm strength and accuracy to the outside of the football field. But we’re forgetting the whole reason that Tebow’s throwing motion was changed in the first place: he was a 23 year old rookie under Josh McDaniels, and was widely criticized prior to the NFL draft based on what I believe to be a non-essential trait of success or failure: that elongated throwing motion. The whole idea with coaching up his throwing motion was that it would positively affect his draft status (and it did). I think Tebow actually regressed as a rhythm/accuracy passer from year one to year two. But because this is year two of Tebow, I think there is a ton of final judgement being done on him as a passer, and I can understand why very little of it is positive. Tebow has shown some ability to place the ball when the throw is within a certain range of arm talent, but down the field and to the edges of the defense he needs a significant window to make the throw.

Even in the case of Tebow, a coaching staff got fired because they built around a whole concept of loading up for the future, and the owner in Denver (Pat Bowlen) did not give ample opportunity for Josh McDaniels and his staff to succeed after multiple early failures. The changes in the organization have really hurt Tebow as a passer. And the Broncos may now have to make a decision on his future as is, meaning that if they decide he’s not good enough from the pocket to lead the Broncos, they may have to go back to the drawing board and find someone who is. The quandary that Tebow has put the Broncos in by running this offense really effectively is pretty much the only thing Tebow can do at this point to save his job. He’s incredibly limited as a pocket passer, and I just don’t think that was the case even one year ago.

Christian Ponder and Andy Dalton had very divergent college careers, and both could have easily gone anywhere between the first and fourth round in the 2011 NFL draft. The Vikings fell in love with Ponder at no. 12 overall, making him a common choice for most overdrafted player based on his perceived draft stock. Andy Dalton got picked 35th overall by the Cincinnati Bengals, who opted not to take him 4th overall based on his perceived draft stock. The Vikings weren’t willing to gamble on Ponder being there later, and the Bengals won their gamble.

And it might surprise you to learn that, according to Total QBR, Dalton and Ponder have been almost the same player. I can attest that Dalton has been tested a lot more early in his career, but Ponder is being forced to improvise to save his offense, and he’s enjoying at least moderate amounts of success. Both Jay Gruden (offensive coordinator – Bengals), and Bill Musgrave (offensive coordinator – Vikings) have put in great work to be able to have rookies lead teams. It’s hard to say how Dalton and Ponder will do down the road since both are looking up at much stronger organizations in their own division that they will have to play every year, and Dalton is 0-2 against the Bengals and Ravens while Ponder went 0-2 against the Packers.

But 2012 will be a big year for both quarterbacks and their coaches. The Bengals are set up really nicely for the future, because they have a ton of draft picks and the Steelers and Ravens are aging rapidly. The Vikings, however, could be playing for Leslie Frazier’s job as soon as next season. And who knows if Musgrave will stay as offensive coordinator for Ponder or take a better opportunity. As much as both franchises have the right to be optimistic after landing quarterback high in the draft that could lead their franchises well into the future, no team is ever more than 365 days away from cold, dark uncertainty. Even if the Bengals make the playoffs this year, it does nothing for them if they fall off the map next year unexpectedly.

All of this brings me to Houston quarterback T.J. Yates, the real point of this article. Yates was a sixth round pick who is probably most famous for being around for practically forever at North Carolina. The guy who may be most sympathetic to Yates’ plight around the NFL would have to be Browns quarterback Colt McCoy. The NFL is a backwards league in many ways, but here’s one you might not have thought of. Tim Tebow is getting tons of criticism for the style of his play, but understand that the criticism is not unfounded, because Tebow is also getting a very legitimate chance to win games, a chance that Tebow would never have gotten if he were a 5th or 6th round pick. T.J. Yates, like McCoy, is precisely that.

The only reason either got a shot as a first year player was due to injury. And unlike first round quarterbacks, mid-round quarterbacks don’t get a chance to screw up. If they struggle in their first opportunity as a rookie, they end up on a backup QB career path or out of the league entirely. Look at Titans’ QB Rusty Smith, who literally got one game to prove himself in the NFL, and was shut out by a historically bad defense. I feel confident in saying that Rusty Smith will never play in the NFL again.

But the whole idea with drafting quarterbacks in the middle rounds is the idea that “developmental prospects” exist. However, this is patently untrue. The difference between middle round quarterback selections and high selections is not the level of development required to turn them into a reliable starter, it is the level of confidence the coaching staff would have to play you as a rookie. It’s almost a curse to have to play as a rookie, but sometimes its necessary: you can’t earn a roster spot through preseason performance alone.

A lot rides on Yates for the Texans. If he plays really, really well, the Texans could have a situation on their hands similar to what the Patriots had with Tom Brady and Drew Bledsoe ten years ago. If he plays poorly, no one in the league is ever going to go out and get T.J. Yates to solve their quarterback issues again. For this opportunity, T.J. Yates had roughly four months from the end of the NFL lockout to the present day to prepare to define his career as an NFL quarterback. He becomes the second quarterback in modern history to get drafted in the sixth round or later and have a legitimate chance to win the super bowl before the age of 25 (Yates will turn 25 in May). He is old for a rookie, and the Texans need to trust him in order to go deep into the playoffs.

To conclude, the primary factor of judging a rookie quarterback is his ability to play quarterback as a rookie. First round picks seem to be able to get two years to show their worth to an organization, everybody else is on a game by game basis. I think this is part a factor of teams having more options at the quarterback position than ever before, and part of it is that some smart coaches showed that you could win right away with rookie quarterbacks, and so the tolerance for losing because of a rookie passer is now a relic in the NFL. Just ask Jack Del Rio.

FNQB: Are Changes in NYPA a Strong Measure of the Strength of Passing Environments?

Not to possibly curb your desire to read the rest of this article, but the answer to the headline question is “not as strongly as I had hoped.” The reasoning behind such a conclusion is that my methodology involved using only the passing performances that qualified at a value between 99 and 101 on the pro-football-reference passing index for net yards per attempt, and the result of the research was ultimately a sample size issue. NYPA is well known as a solid predictive measure of quarterback/offensive aptitude, and so by taking players who were almost perfectly average in this measure between 1970 and 2010, I wanted to see if we could get a good context for the strength of passing in the NFL over the last 40 years. Still, I have plenty of interesting observations to offer.

The main problem is sample size earlier than 1970. I had roughly assumed that in any given season, one out of the 25ish passers who threw a majority of their teams passes would end up roughly at league average in YPA. The accuracy of my methodology makes it back to roughly 1977. This is a bit problematic, because the passing environment very famously loosened in 1978 with the enactment of the “Mel Blount rules” for cornerbacks, rules that were reemphasized in 2004 in a movement lead by the Colts. Obviously, I’d like a better sample from 1977 and before, but the “perfectly average in NYPA” method skimps here.

What we can tell about the pre-Blount rules era is best captured by completion percentage, a value that hardly ever exceeded 53% amongst league average passers in the mid seventies. Although the baseline today is now around 62%, exceeding 60% in the sixties and seventies meant your name was “Tarkenton,” or “Jurgensen,” or “Anderson.” Passers who, in a couple of words, were clearly ahead of their time. After 1975, that began to relax a little bit, and great teams started to have high efficiency offenses, so you’ll see guys like Terry Bradshaw and Ken Stabler with some excellent seasons in the seventies.

If we move our focus to a 16 game NFL season beginning in 1978 with relaxed passing rules, it’s just not clear that the average QB season has resulted in more recent names doing the most to throw their teams to victory. Take a look at the list of average NYPA seasons re-sorted by yards per attempt efficiency. David Garrard last season ranks no. 1: the best yards per attempt in the last forty years by a player with an average season. He is followed by a number of players from the mid eighties: a couple of Neil Lomax seasons, a Warren Moon year, and a Ron Jaworski season. Then we end up in the middle of this decade. Anyway, sorting by yards per attempt puts the results all over the map, and doesn’t really do anything to define an era. The variability of sacks by player doesn’t fall neatly along era lines. And that is why sorting by yards/attempt efficiency doesn’t work.

Actually, this is where passer rating can really help. Here is the same list sorted by passer rating, a metric that doesn’t involve sack rate in any way, but does a good job capturing the increases in the efficiency of NFL passing games thanks to declining interception rates. One of the main observations of this project is that, since 2007, it’s quite common for a player with an average showing in NYPA to put up an 80.0 or better in quarterback rating. Prior to 2007, it was relatively uncommon for a player’s QB rating to exceed 80 if his NYPA was average. Since then, it’s happened 10 times.

Rating also shows us that, while there was a measurable late seventies bump in passing offense, it was short lived. Passing totals REALLY opened up in the mid-eighties, and the truth is (as YPA shows above), NFL defenses were vastly behind for a period of four or five years. There was probably no larger offense-defense discrepancy (at least in favor of offense) than in the mid-eighties when the Chicago Bears could stop anyone they wanted and every other team could score. QB rating shows us that from 1983 though 1988, the average QB season came in steadily above the 75.0 passer rating line for the first time with the average QB completing about 58% of his passes. Those numbers look light today, but defenses are actually a bit better at preventing yards now than they were in the eighties. It was not at all uncommon to average over 200 passing yards per game for the entire season.

I don’t really know why offensive passing numbers stagnated in the early nineties. If I had to venture a guess, I would suggest that the offensive-defensive discrepancy seen in the mid-eighties closed, perhaps of factors and adjustments that we would suggest to be rather normal. I do know that 1994 was an aberration year because a bunch of hall of fame quarterbacks had career years, pushing the average passing year towards the levels we currently see in the NFL. Following the passing explosion in 94-96, offensive passing totals were pretty stagnant between 1997-2002.

The NFL has been a decidedly different game ever since totals bumped between 2003-2004 and then similarly in 2007-2008. For the first time since the eighties, we can accept seven yards per attempt to be the standard for passing. But even then, passing wasn’t necessarily efficient. It was simply accepted in the 80s that 4ish percent of a QBs passes were going to get picked. As it became wise to start trading some raw yardage efficiency to take fewer negative plays (sacks, picks), defenses caught up. But teams got really good at maximizing sack and interception efficiency in the mid nineties to early aughts to the point where passing became an equal or superior option to running the football league wide. And as the quality of the talent pool saturated with passing and receiving talent after the 2002 season

Back to the top, NYPA isn’t a great measure of era strength, perhaps because it’s too predictive of a measure. Young players who did average in NYPA typically played a lot more above average years. Old players who were average in NYPA were near the end of their careers. It wasn’t easily sortable to the point where the raw number gave a great snapshot of how passers were doing in that season. I will point out that Adjusted Net Yards Per Attempt correlates almost perfectly with the time horizon examined in this article.

Everything I learned here suggests that passing cycles are cyclical: predictive efficiency (NYPA) ended up as not a great measure of era efficiency because of sample size issues. Adjusting for interceptions and touchdowns fixes the variance in the sample and shows a long-term linear trend in passing efficiency. That’s fascinating because it suggests that as offenses have gotten smarter over the years, the defenses have been unable to force offenses (as a group) to negatively trade off points or yards. For example: it suggests that defenses are helpless to try to swing offensive efficiency in the other direction by increasing sacks or interceptions or passing touchdowns at the cost of yards against.

And despite this, NYPA was identical in 1979 as it was in the 2000s. The Blount rules had a huge, unbreakable effect on average NYPA, broken only by the unprecedented efficiency in passing we are seeing in the NFL since 2008. Overall leaguewide passing efficiency, however, started a steady climb then and was undeterred on a league level throughout fluctuations in yard and points expectancy. Scoring totals, keep in mind, correlate almost perfectly with passing YPA because increased INTs and Sacks (things not captured in YPA) don’t discourage scoring overall, they encourage scores by the defense.

The passing era of the modern (since 2007) NFL is historically unprecedented. Offenses have never been more efficient, and defenses have never had less of an effect on overall offensive efficiency. We’re now seeing 30-year long offensive efficiency rates begin to break in the offenses favor. This is exciting stuff if you happen to be a football history buff. Despite the sky high offensive efficiency rates, scoring totals will never match the levels of the 1950’s and 1960’s because offenses are now able to keep defensive scoring to a historical minimum. Despite that, teams are now scoring as much as they did in the 1980’s, when the passing environment was fertile, but also led to high turnover totals and short fields for the other team. Net yards per passing attempt really didn’t predict any of this: it said pretty much the same thing about offensive power from 1978 through 2006: 5.8 or 5.9 net yards a play. In the future, however, it might be the best indicator we will have to go on.

All statistics used in this article are courtesy of profootballreference.com

FNQB: NFL’s Projected $130 million Salary Floor is going to Render Recent SB Winner Roster Models Obsolete

Reports from the ongoing NFL CBA negotiations agree that the next NFL collective bargaining agreement is that the players will now receive 48% of total NFL revenues. If that sounds like a pay cut from the prior level of 60% of total NFL revenues, it is. But barely. The owners are apparently willing to agree to take that $1 billion league expense credit and throw it out, meaning that the 48% of total revenues for the players will actually be 48% of total revenues.

We can do some dirty math and calculate the expected NFL salary cap in 2011. $9 billion in total league revenues times .48 for the players’ share is $4.32 billion. Divide that share into 32 teams gives us a per-team cap of $135 million. That’s a good, accurate projection for the salary cap. It’s also roughly equal to the salary cap in 2009, which makes some sense. Revenues have increased, and the owners are saving something in this deal, so $135 million/team is a good salary cap figure that doesn’t put any strain on teams to cut salary after the uncapped year in 2010.

On the contrary, there will be a salary strain on plenty of organizations in 2011. And it’s not going to be the free-spenders who don’t always compete such as Washington and Minnesota. It’s likely to be the penny-pinching, player development focused franchises who are wildly successful, as well as the small-market, resource-limited teams that bargain hunt frequently. Because it also appears that the owners and players will be agreeing to an aggressive salary floor. This floor is expected to be set at 46.5% of total revenues. Doing the math precisely the same way as before, we find that the NFL salary floor in 2011 is expected to be set at $130.7 million dollars per club.

You think that’s going to change something? Understand now that as we currently stand, practically zero teams are in compliance with that salary floor in the uncapped year. Does that make any sense? The NFL had a year where the spending of teams was not limited (though player movement was). The Cowboys and the Redskins exceeded $165 million in salary. No other team got close to them. PFT has the list of salaries last year. 11 teams, one-third of the league, exceeded the SALARY FLOOR set by the NFL this year. 21 teams would not have been in compliance with such an agreement in 2010.

Redskins: $178.2 million.

Cowboys: $166.5 million.

Saints: $145.0 million.

Vikings: $143.4 million.

Seahawks: $138.8 million.

Jets: $135.7 million.

Packers: $135.3 million.

Raiders: $135.2 million.

Colts: $133.1 million.

Bears: $131.9 million.

Eagles: $131.0 million.

So 2/3rds of the league must change their behavior starting this belated offseason, and spend a higher percentage of revenues on players. And a number of the complying franchises are playoff teams. For most of the current playoff contenders, complying with the salary floor essentially means making a big free agent signing who fits the scheme, and rolling over the budget year to year. There are a number of teams who aren’t all that close to any sort of salary floor (I think the last salary floor sat around $95 million in 2009), and it’s hard to envision the plan for building these teams to included dumping a ton of annual salary into any veteran that can be reasonably expected to make the team. Take a look:

Panthers: $110.9 million.

Rams: $109.1 million.

Chargers: $108.0 million.

Bills: $105.3 million.

Broncos: $102.9 million.

Bengals: $100.8 million.

Cardinals: $97.8 million.

Jaguars: $89.5 million.

Chiefs: $84.5 million.

Buccaneers: $80.8 million.

This is going to be tough for these teams. It cannot be assumed that any of these organizations are going to be serious competitors for the premier free agents, yet, they are all going to need to come up with a way to raise salary by up to $30 million in 2011. This isn’t baseball. It is difficult to spend that much money in general. To do it without hurting ones team almost requires a $70 million total value contract to a franchise cornerstone. If you’re the Bucs or Chiefs, well, okay. You can find someone to give those millions to. But if you’re the Bills, Jaguars, or Bengals? Being forced to go outside the organization to give the big bucks away is really dangerous because all the good teams will be after the players who can justify that type of money with their checkbooks. Obviously, this leads to the two main mistakes: overpaying for mediocre talent and creating an albatross contract, or bidding up the price on a number of mid-tier signings, obstructing draft picks.

Despite all the extra money that is going to be in the game for players, I’m not figuring that there are going to be a great number of players who are looking forward to accepting starter money and a backup role. Not the veterans who will be eligible to get such contracts. With extra money in the game, veterans will be able to hold their spots longer. This is good for NFLPA members, but it makes building from youth a lot more difficult for the clubs. Oh, and did you here they are capping rookie salaries? This is going to work out great.

When you think about how the recent super bowl winners have been built, the formula is typically a well-built, homegrown defense with a quarterback drafted in the first round, and an intelligently built offensive line that gets the job done. We’ve seen teams like the Jags and Chiefs — to make a much easier salary floor in 2009 — pay non-elite passers like elite quarterbacks. That’s the salary floor effect that we’re going to see in spades this year.

It’s not a big deal for the Bucs, who can just give Josh Freeman an $100 million dollar extension before the season to raise payroll: they know he’s their future anyway. What about the Jags, who even when they keep David Garrard for this season, still need to raise payroll? So they keep Garrard and start him. They keep Aaron Kampman as he rehabs from another knee injury, because he helps up their salary. They keep Derrick Harvey, their 2008 first rounder, even though they are no longer sold on him as a starter. They can go out on the free agent market and finally buy some much needed secondary help. They extend MLB Kirk Morrison. The Jaguars become big spenders. And they only have $15 million to go in order to make the NFL salary floor! It’s okay: payroll is a marathon, not a sprint. Teams just have to tough it out.

You can’t blame the players any for wanting a high salary floor to ensure that money pumps through the game, even if teams can no longer build optimally. My hope is that this results in longer, bigger contracts for young players with plenty of upside, and that teams will now stop giving up on their players so early, if only because they need to make the decision to commit to them earlier then ever. For the non-rookie players, there is no downside to a high salary floor. For teams, it’s going to be a problem. And I just can’t say I’m all that surprised that they don’t see it yet.

FNQB: Having No Quarterback is Not an Excuse for Lack of Offensive Improvement

This article is about the Washington Redskins and the Cincinnati Bengals, but really, it’s about 17 different NFL teams. This is about teams that try to win without established play from the quarterback position, and why its imperative to realize who is and isn’t being hurt by the inability to develop a quarterback.

The trends in the game strongly show that the “haves” in the game get production out of their quarterback position, while the “have nots” often do not. The correlation isn’t as perfect as some would lead you to believe, but it’s there and it’s at least very clear. The NFL’s have nots in the last decade have included the Lions, Redskins, 49ers (post-Garcia/Owens), Cardinals (pre-Warner/Fitzgerald), and the Vikings in the NFC, and the Raiders (post-Gannon), Texans, Bills, Dolphins, Browns in the AFC with the Bengals as sort of a weird Rorsach test. The evidence shows that even the most moribund of franchises come out of the doldrums with a good QB year (such as 2007 Anderson, 2008 Warner/Chad Pennington, 2009 Favre).

But far too often, we mess up the cause and effect of quarterback play and team performance. The Lions and Redskins both endured some of their worst seasons (2006, 2009 for Washington; 2004, 2008 for Detroit) with some of the best QB play in recent memory by either franchise. The problem here is that good but not great QB play is almost not correlated at all with wins and losses, but where wins are, we find ways to inflate the true performance of the QB. What was the difference between Kyle Orton and Josh Freeman’s 2010 seasons? I think Freeman was a bit better in the pocket, but one QB won 3 games and lost 10 (and his job), and the other won 10 games and lost 6. And Freeman was, at best, marginally better (though the *promise* of future dominance is a big concern here). Freeman ended up on the Top 100 list of NFL players in 2011, and Orton is possibly going to lose his job to either Tim Tebow or Brady Quinn. Is that outcome really following all the available evidence? Not until wins and losses are included, it isn’t.

There have been “have nots” with very efficient QB play in recent years: the Redskins under both Mark Brunell and Jason Campbell, the Bengals under Carson Palmer, the Vikings under Daunte Culpepper, then Brad Johnson, and later Brett Favre, and the Dolphins under Chad Henne. The Rams had a lean period from 2004-2006 with Marc Bulger still playing well. Meanwhile, teams win all the time with below average QB play. The Jets have taken Mark Sanchez to the AFC Championship game in consecutive years. Ignoring future development potential (a major consideration, I admit), the Jets would have been better off (and were with Favre and later Brunell) with any of the names listed in this paragraph above over Sanchez. They won though, making this a moot point and Sanchez a cult hero. The Giants won a bunch of playoff games including the greatest team of all time (not to win the big one), the 2007 Patriots, simply because a developing Eli Manning stopped throwing picks in the playoffs. Like people feel can happen with Sanchez, Manning DID develop. The Cowboys made it into the playoffs in 2003 with Quincy Carter at the helm. Jake Delhomme and Michael Vick both won enough games to take the AFC South in 2003-2005. The last decade of Bears and Ravens teams featured many, many playoff runs with zero year to year consistency at the QB position (Flacco may, finally, be a keeper). Getting Jay Cutler to be the franchise QB hasn’t exactly gotten the Bears any closer to the goal of winning the super bowl. They still knock on the door every year. Kurt Warner, very possibly, isn’t a hall of fame caliber quarterback if he doesn’t join the NFC West division just as it enters the leanest period since realignment. And look back on Donovan McNabb’s career through the prism of his 2010 season, and consider how long he may have lasted if the NFC East wasn’t such a pushover division before Eli Manning and Tony Romo and Joe Gibbs.

The quarterbacks who played for the “have not” teams didn’t fail to win because of any personal flaw in there game, perhaps short of simply not being transcendent players. Throughout Vince Young’s career, the relationship between his performance and playing time has been inverse. Young actually was a transcendent college player, and the more he developed in the NFL, the larger of a pain in the ass he became. For Cutler, at least it’s the opposite: he’s a pain in the ass when he’s not playing well, but a good face of the organization when he is. Matt Leinart hasn’t played…at all.

The factors at play here don’t obviously have a lot to do with the quarterbacks themselves. It seems to have more to do with the organizations. A couple specific types of organizations have failed.

Organizations that lack overall resources to succeed

You probably didn’t realize that this made any difference in the NFL where every team can spend to the salary cap if it so pleases, but a number of orgs simply don’t have a lot of their own resources. The Cincinnati Bengals, the Buffalo Bills, the Minnesota Vikings, and to a lesser extent, the Detroit Lions, Jacksonville Jaguars, Tampa Bay Buccaneers, and San Diego Chargers (and for a very long time, the New Orleans Saints — though the environment there may have permanently changed for the better) simply have a bottom line that affects their football decisions. None of the teams that have won with poor quarterback play over the last decade (the Bears, Ravens, Giants, Jets) have any sort of resource problem what-so-ever. Those organizations more or less print money.

But think of the three or four most financially insoluble franchises of the last ten years. The Bengals had the first overall draft pick once and picked Carson Palmer. The Bills have never had the first overall pick. The Vikings have never picked higher than 7th in the last decade. The Raiders picked 2nd overall in 2004 taking Robert Gallery and 1st overall in 2007 taking JaMarcus Russell. And think how frequently impaired these rebuilding projects have been:

- After winning 11 games in 2005, the Bengals tried to build up a competent defense through the draft exclusively. While they were eventually successful, the 2009 playoff version of the Bengals was dealing with a damaged goods Carson Palmer at QB, losing TJ Houshmandzadeh in free agency, a declining Chad Ochocinco, and having to rebuild the entire OL on the cheap (making a rare sign-ability pick in OT Andre Smith in 2009). More directly, the Bengals have long tried to find a Moneyball-style market niche in players that other teams avoid due to character concerns. These moves haven’t often paid off. The approach has cost them their franchise QB to retirement. This does NOT happen to franchises with resources.

- The Buffalo Bills have never picked higher than third in a recent NFL Draft, and never once were able to offer anything resembling a trade up to position themselves for a quarterback since 2004, when they traded their 2005 first round pick to draft…JP Losman. The 2004 Bills were the best Bills team since the Jim Kelly days, so they ended up trading the 20th overall pick in the 2005 draft, which could have easily been Aaron Rodgers. Since Losman busted, that’s really not all that relevant. Here’s who the Bills HAVE passed on since 2004 at QB: Matt Leinart, Jay Cutler, Brady Quinn, Joe Flacco, Josh Freeman, Jimmy Clausen, Tim Tebow, Colt McCoy, Jake Locker, Blaine Gabbert, and Christian Ponder. Would any of those players have prevented the Bills from being another resource-limited franchise that cannot develop a QB? Each player on that list outside of Quinn and Gabbert would have been considered a reach when the Bills selected, and the Bills have done a good job of being selective regarding their quarterback in the current market conditions. They just haven’t drafted well enough to improve outside of the QB position.

- The Minnesota Vikings push the limits of the salary cap every year, which they can do because of revenue sharing, and has allowed them to maintain a number of defensive superstars such as Kevin Williams, Jared Allen, and Antoine Winfield, while still drafting very good players on that side of the ball such as Chad Greenway and EJ Henderson. DC (now HC) Leslie Frazier has generally made very good decisions on his side of the ball. But the limited resources of the Vikings — which includes a sale of the franchise and the inability to land a new stadium — have cost them offensive stars such as Randy Moss and Daunte Culpepper, who actually have been adequately replaced in the short term with Nate Burleson and Brad Johnson. Then those guys left and what was left was some sort of bastardized west coast offense build by Brad Childress that both featured and refused to feature Tarvaris Jackson at quarterback. The Vikings should have been dominating the NFC North between 2005 and 2009, between the primes of Brett Favre and Aaron Rodgers, but the Chicago Bears in many ways just out-resourced the Vikings for that opportunity. There’s no other logical reason that the team with the best offensive and defensive players in their division in 2007, 2008, and 2009 won the division just twice and won just a single playoff game.

- There are no question the Oakland Raiders often acted erratically under Al Davis over the past decade, and rarely have they built anything positive, but the Raiders have done a far better job of resource-limited franchises of spending to win based on their scheme. Even the Raiders, however, departed from wise spending during the Lane Kiffin era, not allowing Kiffin to pick his QB in the 2007 NFL Draft, and then unjustly spending on defensive players Kiffin asked for to save a job in 2008 that Davis was hardly committed to. The Russell mistake is well documented, as is the Randy Moss error, but why did the Raiders go after DeAngelo Hall and Gibril Wilson in 2008 free agency when the team had done nothing but draft players in the secondary over the drafts leading up to this one? And worse, when the Raiders released Hall after jettisoning Kiffin, they moved back to a man coverage scheme where Hall could have excelled. The Giants could have overcome such a waste, but the Raiders just are right now. The Raiders regathered their resources after that season and have seemed to have gotten it right: no team in the NFL is loaded like the Raiders are now, although to this day, the Michael Huff pick in the 2006 draft is going to set the franchise back as much or more than the JaMarcus Russell pick as the team passed on a transcendental DL in Haloti Ngata who fit the Raiders scheme.

Meanwhile in 2009, the Lions and Bucs both started streamline rebuilding projects that have produced far improved organizations who use their resources wisely. The Chargers, for all the crap that general manager AJ Smith takes, have been doing this for years and are still a model organization. The point is that you can win with limited resources in the NFL, but conventional wisdom is almost always designed to get teams off track. And as the next section proves, even having resources doesn’t ensure success once a team has a quarterback

Organizations that are Poorly Managed

This is where it makes sense to introduce the cases of the Washington Redskins, the Cincinnati Bengals, and the Miami Dolphins. Even when these organizations hire good people (Bruce Allen, Marvin Lewis, Bill Parcells), they cannot seem to sustain any sort of meaningful gain from it. Because for these three organizations, hiring good people is the abberation, not the rule. And so short term gains remain just that, short.

Parcells, prior to leaving the Miami Dolphins, was able to restock his team’s roster at quarterback by picking up Chad Pennington and adding Chad Henne in the draft, and doing so in a manner that allowed him to add Jake Long with the first overall pick in 2008 to bookend Vernon Carey as the AFC’s top offensive tackle tandem. Ignoring the high efficiency backs that Miami already possessed, the Dolphins were flat handed the structure of an elite offense and an attacking 3-4 defense that had all meaningful parts in place, could develop talented, low-cost role players, such as Cameron Wake, and had high efficiency receivers in Davone Bess and Brian Hartline who went undrafted, and provided punch to the Dolphins offense without cost.

So you tell me: how did that team end up closer to the resource-less Bills in overall results than the AFC playoff bound New York Jets? After the sale of the team from Wayne Huizenga to Stephen Ross, and the departure of Parcells (who wouldn’t have helped the ‘get over the hump’ process anyway), the Dolphins have managed to sink to one of the worst run organizations in football. Sparano has voluntarily taken the ideal QB situation of Pennington-Henne and has added Tyler Thigpen to the mix, not-so-inadvertently (but completely unnecessarily) making QB a question mark in 2011. The team traded for Brandon Marshall in 2010, who cost them two second round picks — which the Dolphins treat like candy on Halloween anyway — and Marshall hasn’t done anything to improve the offense while undermining his quarterback.

The Dolphins have at least managed to not sabotage their infrastructure: that defense looks like the early favorite for the best in 2011. But the offense is a mess despite every advantage one could possibly have, and I can’t see the Dolphins winning in 2011 even if they feature the leagues best defense. It will all be put on Henne, but the criticism belongs higher up. On Ireland and Ross.

The Cincinnati Bengals have something to prove in 2011, that they can win without Carson Palmer at quarterback. But they’re not just fighting common perception that teams can’t win in the NFL without an established quarterback, they’re also fighting their own organization. It is possible that the Bengals turned over a new leaf starting with the 2011 NFL Draft, picking AJ Green and Andy Dalton with their first two picks. But the team is proving unwilling to turn it’s most valuable asset, Palmer, into picks and players that can help the Bengals win in future season. Meanwhile the team is all too ready to do exactly that what it won’t do with Palmer with star receiver Chad Ochocinco, but Ocho has virtually no value as a trade piece.

It’s very clear looking at the Bengals roster that they plan to rebrand themselves as a ground-first team, which is a good idea, but it also seems like the team is just waiting for the end of the lockout to make 28 year old RB Cedric Benson the highest paid player on their offense, which is a terrible idea for a number of reasons, not the least of which being that Benson is a 28 year old RB. The team may not be able to afford Jonathon Joseph at corner, who is an impending free agent. The resource limited Bengals are just poorly managed enough to seriously consider spending the balance of those resources on Benson. They may be able to win in 2o11 behind a strong offensive line and a renewed passing game, but I don’t know if the trigger man of the offense can be either Jordan Palmer or Andy Dalton this year. I think they need a third party. And I don’t know if the Bengals have a plan to win in 2011. Which is expected, because these are the Bengals.

Remember: the Bengals did not win when they had a quarterback (and a passing game). As good a pick as AJ Green is, keep that in mind when evaluating the career potential of Andy Dalton in Cincinnati.

Really though, this point is about the Washington Redskins. It’s about Mark Brunell and Jason Campbell. It’s also about Donovan McNabb, Rex Grossman, and John Beck. It’s about Dan Snyder, Vinny Cerrato, Jim Zorn, Mike Shanahan, and Bruce Allen. It’s about the quarterback “excuse.” The defeatist Dolphins complain that not having a quarterback is holding them back, and have for a decade, save 2008. The Bengals have their finger on the button, ready to pull the same excuse. But no team has been worse than the Washington Redskins at pulling the quarterback excuse to place the blame anywhere but on themselves.

Like the Dolphins, an ownership sale really did hurt the team’s ability from a resources perspective to lock up that quarterback situation. The year was 1998, and the Redskins — for a couple of critical months, at least — were resource limited. The quarterback in question was Trent Green, who signed in St. Louis as a free agent, and followed around Dick Vermeil for the rest of his career. So the Green thing fell apart for the Redskins because of a resources situation. And as written above, teams should get a pass, within reason, for being resource limited. And it cost the Redskins Green.

What then, is the excuse for: Brad Johnson, Patrick Ramsey, Mark Brunell, Jason Campbell, and Donovan McNabb? Because it’s now 2011. And the Redskins are still using the same “quarterback barren” excuse that died after Johnson replaced Green in 1999 twelve years later. And five physically capable quarterbacks have walked through the doors in Washington, enjoyed a successful-mini career, and mind you, the Redskins organization is in no better shape than the day they brought Jeff George in to “solve” the problem that never existed in the first place. Johnson, Ramsey, and Campbell all cost the Redskins first round picks. McNabb cost a second and a fourth. Brunell cost a third and a fourth. None were apparently worth a commitment. And the product of those ten years were a lot of losing, three playoff games, and an offseason debate as to whether John Beck or Rex Grossman is more deserving of succeeding McNabb.

You could argue that no team has had more resources than the Redskins under Dan Snyder, and it’s almost inarguable that no team has done less with it’s available resources than the Redskins. This proves that while teams lacking resources are always struggling to sustain, teams with resources will be no less likely to fail if managed poorly. I’m trying to think of any other team that has the sheer quantity of quarterbacks come through that would either go on to enjoy more wins (Johnson, Campbell), or had come from very successful programs with no real success (Brunell, McNabb). Tampa Bay, maybe? They had Freeman, Garcia, Johnson, and…Griese/Gradkowski? Chris Simms is too much of a stretch. What about Denver? Griese, Plummer, Cutler, Orton, Tebow? The Giants had Kerry Collins and Warner, and culminated with Eli Manning.

It is somewhat fitting that the 2010 Washington Redskins’ front office was comprised of the personnel guys for the only two other teams not able to establish quarterbacks with a comparable level of talent coming through the organization at the position. It’s fitting really. And it leads me to the big point: under no circumstance is instability at the QB position ever a good excuse for not making offensive improvement. It never is. Good quarterback play, by itself, never solves organizational issues. Organizations that turn themselves around typically do it with the combination of good quarterbacking and something else. If the Saints, perhaps the most recent example of an organization that turned itself around, had made the NFC Championship game in 2006, but failed to hire Gregg Williams in 2009 and had languished any further on defense, it’s not clear if Sean Payton would still have a job and if Drew Brees would still be worth an enormous salary. The Saints found offense, but they also controlled the next step in becoming a super bowl champion when the organization stopped shooting itself in the foot. The Jaguars, who did not bother to retain Williams after the 2008 season, have declined on defense since.

I would almost be wasting my time to remind you that when the Redskins made the playoffs twice in three years in the middle of this decade, Williams was calling their defense, and the Redskins were using their considerable resources to get him pieces. Unfortunately, a poor year by the defensive unit in 2006 caused the Redskins to…get this…blame it on the quarterback (Brunell), and make a change there. The Redskins blew up shortly after Williams left as an organization, and Jason Campbell was left with the task of picking up the pieces.

Teams that have resources, in particular, should win. The Redskins should win. The Dolphins should win. The Cowboys should win. The Bears should win. The 49ers should win. The Titans should win. The Broncos should win. The Texans should win. It’s the natural order of professional football. Whether these teams have a quarterback or not, or are simply in between quarterbacks, it’s not an excuse. Twelve teams make the playoffs each year, and not all of them do it with great quarterback seasons. However, for organizations that don’t do very much well, they typically find fault with the QB position very quickly relative to other positions. But having an abundance of resources means that if you address all your issues at once, there is enough time and money and coaching and scouting to go around to create a winner. Teams like the Bucs and the Chargers have to streamline operations specifically because there aren’t enough resources to do everything at once like a large market team can do. But when teams like the Redskins and Dolphins push past a decade of incompetent decision making, despite the ability these teams have to error and recover quickly, you do have to glance over and chuckle when people want to point out that the quarterback situation isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

FNQB: How well would Tom Brady Profile as a Draft Prospect Today?

This week’s Friday Night Quarterback question is one that attempts to answer the question of where Tom Brady would profile in the NFL Draft if he had come out of Michigan in 2011 instead of 2000. You know the background story on Brady. He was recruited to Michigan and buried on the depth chart, but emerged as the best player for the job in 1998 after Michigan won the national championship, starting the final 25 games of his NCAA career, and winning 20 of them including two major bowls. Brady, though, played for Michigan in such a dominant era that he never received the reputation for being a good college player.

Brady’s scouting report, which is unsourced primarily because it is eleven years old, reads as follows:

Notes: Baseball catcher and football quarterback in high school who was drafted by the Montreal Expos in the 18th round of the June 1995 baseball draft. Opted for football and redshirted at Michigan in ’95. Saw limited action in ’96 and ’97 and started the past two years. Completed 3 of 5 passes for 26 yards, no touchdowns and one interception in ’96, 12-15-103-0-0 in ’97, 214-350-2,636-15-12 in ’98 and 180-295-2,216-16-6 in ’99, when he often shared time with super sophomore Drew Henson. Went all the way against Alabama in the Orange Bowl and completed 34-46-369-4. Unlike many Michigan quarterbacks, Brady is a pocket-type passer who plays best in a dropback-type system.

Tom Brady Positives: Good height to see the field. Very poised and composed. Smart and alert. Can read coverages. Good accuracy and touch. Produces in big spots and in big games. Has some Brian Griese in him and is a gamer. Generally plays within himself. Team leader.

Negatives: Poor build. Very skinny and narrow. Ended the ’99 season weighing 195 pounds and still looks like a rail at 211. Looks a little frail and lacks great physical stature and strength. Can get pushed down more easily than you’d like. Lacks mobility and ability to avoid the rush. Lacks a really strong arm. Can’t drive the ball down the field and does not throw a really tight spiral. System-type player who can get exposed if he must ad-lib and do things on his own.

Summary: Is not what you’re looking for in terms of physical stature, strength, arm strength and mobility, but he has the intangibles and production and showed great Griese-like improvement as a senior. Could make it in the right system but will not be for everyone.

We know these there are three variables that translate directly from the college game to the pro game. First: college completion percentage. Second: college sack rate; at the major college football level (the proliferation of the spread offense at lower levels of college football has rendered this measure useless for lower-division QBs, though the skill is still important). Third: the adult height of the quarterback. We know that all other college stats are system/situation dependent enough to not have any predictive value between a college quarterback and that same players in the pros. But we also know that a player’s stats are largely useless in a limited sample which is why three and four year college starters are so much more valuable in the draft today than one or two year starters.

And that’s the big thing with Tom Brady. He was a great statistical quarterback at Michigan, but because his career lasted only 25 starts, it was easy to write his production off as a function of his team’s dominance, and his physical skill set as alluded to in his scouting report, only served to reinforce the idea that any player could have accomplished what Brady did at Michigan over his timeframe. It wasn’t a certainty that he was going to get drafted in 2000, though it was pretty likely.

What sticks out about the Brady scouting report was that he was labeled as a system quarterback by the scout, a label that has pretty much held up as true in the pros. Brady has become a system quarterback, the first elite spread quarterback in the NFL in the way that Joe Montana became the first elite west coast quarterback in the NFL. Guys who are viewed as system passers, such as Colt McCoy or Kevin Kolb, almost universally do not get picked in the first round. I needed more context on this, so I looked up the scouting report of a guy who has had a very similar career to Brady in the same NFL era, but didn’t fall to the sixth round.

Drew Brees

By: Dave-Te’ Thomas#15-DREW BREES Purdue University Boilermakers 5:11.7-221

ANALYSIS

Positives… Touch passer with the ability to read and diagnose defensive coverages…Confident leader who knows how to take command in the huddle…Very tough and mobile moving around in the pocket…Has a quick setup and is very effective throwing on the move…Throws across his body with great consistency…Hits receivers in stride and improvises his throws in order to make a completion…Puts good zip behind the short and mid-range passes…Shows good judgement and keen field vision…Has a take-charge attitude and is very cool under pressure…Hits receivers in motion with impressive velocity…Has superb pocket presence and uses all of his offensive weapons in order to move the chains…Has solid body mechanics and quickness moving away from center… Elusive scrambler with the body control to avoid the rush.Negatives… Plays in the spread offense, taking the bulk of his snaps from the shotgun… Tends to side-arm his passes going deep…Lacks accuracy and touch on his long throws… Seems more comfortable in the short/intermediate passing attack…Does not possess the ideal height you look for in a pro passer, though his ability to scan the field helps him compensate in this area…Will improvise and run when the passing lanes are clogged, but tends to run through defenders rather than trying to avoid them to prevent unnecessary punishment.

CAREER NOTES

The unquestioned leader of the Boilermakers’ offense and one of the school’s most decorated athletes…The three-year starter shattered virtually every school passing record and also made his marks on the Big Ten Conference and NCAA Division 1-A record charts…Ranks fourth in NCAA annals with 1525 pass attempts, 942 completions and 11,815 yards in total offense (NCAA does not recognize bowl stats)…Including post-season action, he holds the Boilermaker and conference career-records with 1026 pass completions of 1678 passes for 11,792 yards, 90 touchdown tosses and 12,692 yards in total offense…His pass completion percentage of .611 set another Purdue all-time record… Only player in Big Ten Conference history to throw for over 500 yards in a game twice in a career…Threw for over 400 yards seven times, over 300 yards sixteen times and over 200 yards twenty-seven times during his career…Tied Wisconsin tailback Ron Dayne’s (1996-99) Big Ten Conference record by earning Player of the Week honors eight times during his career.

Drew Brees is kind of sort of a system quarterback, though in a far different way than Brady. Brees’ accuracy numbers are all about the precision on his passes and fitting the ball into tight spaces. Brady’s accuracy numbers are about being ahead of the defense from a mental standpoint and quicker than the defense with his arm. The reason that Brees was selected in the second round was that he did a ton of passing in his four years of college. As you read above, his size and durability were a concern, and like Brady, scouts weren’t convinced he could be an effective vertical passer coming out of college. The difference between Brees and Brady was that college senior Drew Brees threw the football in the intermediate zone and to the sideline in a way that made scouts very confident that he could translate to the pro game given a top rushing attack (which he had in SD), by making the difficult out throws that NFL quarterbacks need to. I feel that Brady’s combine performance may have given some credence to the thought that he could not make those throws to the edge of the football field. Otherwise though, these were eerily similar prospects coming out who have enjoyed very similar careers, except that Tom Brady got overlooked on Draft day, and Brees was the second quarterback in 2001 taken after Michael Vick.

A first round pick in today’s game must be perceived as durable coming out of college. Joe Flacco was perceived as durable. Sam Bradford, despite a shoulder injury, was perceived as durable. Blaine Gabbert: durable. Matt Ryan: durable. JaMarcus Russell: durable. Brady Quinn: durable. Even Matthew Stafford was perceived to be durable coming out of Georgia. Neither Brady nor Brees seemed like they would hold up to the NFL rush, and Brady’s frame was of particular concern. Of course, Michael Vick went first overall in 2001 as an anomaly because no one could have possibly felt he was durable. If we expand the scope past quarterbacks, Reggie Bush may have lost out on being the first overall pick because of durability concerns at the next level.

So we can conclude that as a system QB project who had durability and arm strength concerns, Brady would not have gone in the first round in any year. There were too many questions about him as a prospect. The second round is possible. Brady had a lot of Drew Brees’ qualities, and a lot of Kevin Kolb’s qualities as well.

Strengths:

Kolb has good size and build for a NFL quarterback and excels at throwing short to mid-range passes. He can throw the ball on the move and is a threat to run with the ball if necessary. Kolb is a great leader and has started for four years at Houston. He would be an ideal West Coast quarterback once he learned the system.

Weaknesses:

Kolb did not play in a pro style offense at Houston and would have to learn the NFL style of progression and reads. He is unlikely to become an elite vertical passer. He must work on improving his mechanics, as he has a tendency to wind up too much. Kolb has as tendency to go to a three quarters delivery that causes the ball to get batted down at the line of scrimmage.Overall:

Kolb was productive at Houston, but that was in a shotgun based, short throwing offense. He would have to take the time to learn the pro style offense, and his lack of arm strength will limit his ceiling. The question on Kolb will be if his success was due to the system or if he can mature into a solid NFL starter.

System concerns. Vertical passing concerns. No height concerns and no durability concerns listed for Kolb, who was definitely not as well regarded as Brees coming out (for Brees the spread system was perceived as more of a fact, re: learning curve; for Kolb, it meant he was off a lot of teams boards). Kolb was more highly regarded than Tom Brady coming out of Houston in 2007 (which ended up being a weak QB class), and I think the reasoning for that is sound. Brady, all these years later, would not go at the top of the second round either.

A good comparable for Brady in terms of historical significance is Joe Montana, and he was drafted 82nd overall in 1979, which was pretty high for a quarterback. The scouts in that draft loved Jack Thompson and Phil Simms, which made 79 a really strong draft for quarterbacks at the time even before you consider Montana. In today’s game, Montana wouldn’t have fallen past where Jimmy Clausen was drafted by the Panthers out of the same school in 2010. But then again, Montana was an accomplished college player who simply had arm-strength/system limitation. In hindsight, Brady had the same deal: accuracy over arm, but was overshadowed at his college program where Montana achieved legend status. Brady was more like Wisconsin’ Scott Tolzien should Tolzien have enjoyed a more competitive performance against TCU in the Rose Bowl, which probably cost him the right to be drafted.

System guys like Michigan-era Brady get drafted if they play in enough big games in their college careers, which Brady did. Strangely, that’s probably not what got him drafted in 2000. Brady’s intelligence made him a perfect candidate for the system that Bill Belichick was trying to install in New England. But because of the success of that system and the proliferation of Belichick’s assistants throughout the league, players with Brady’s skills are more valued today. Brady’s draft profile would have been more valuable than, to throw a name out there, either Colt McCoy or Mike Kafka in 2010.

We now have a range where Michigan’s Tom Brady would have been drafted in the 2011 draft. He would have gone higher than Joe Montana went in 1979, because players who were more maligned by NFL draftniks and front offices alike slipped further than that.

I went back to the list of statistical comparables, and I see names like John Beck, Jimmy Clausen, Drew Stanton nearby in completion percentage. This year, the closest comparables were Andy Dalton, Christian Ponder, and TJ Yates unadjusted for era, and Tolzien and Greg McElroy when compared to the time-weighted average. Brady would have been one of the more sought after system quarterbacks this year, though he probably wouldn’t have caused the Dalton-mania symptoms the Bengals exhibited on draft day. I think he would have gone higher than the average year in 2011, but speaking about 2011 more abstractly, I think Brady would have been the fourth QB drafted in 2009, I think he would have been the third or fourth QB taken in 2010, and he probably wouldn’t have been in the first five taken in 2011, though that would have been the one year Brady might actually have gone in the first round.

Tom Brady, a decade later, would likely not have been a sixth round pick. Brady likely would have been perceived similar to this years former Michigan QB, Arkansas’ Ryan Mallett. Brady may not have been seen as the player with the most upside, but he wouldn’t have fallen due to character concerns. If Tom Brady had not been drafted in 2000, but had been drafted in 2011 or 2012 instead, front offices would have rated the Michigan product as a mid second round pick to an early third round pick, and a system quarterback prospect who could thrive in a system that takes advantage of his limited skill set.

Like, for example, the New England Patriots.

FNQB: What Kind of Trouble is Jimmy Clausen Worth?

One of the decisions that the Carolina Panthers will have to make in deciding whether to select a quarterback is whether or not 2010 second round pick Jimmy Clausen is worth playing for another year. Clausen just wasn’t good at all as a rookie in 2010, but as a rookie playing with many other rookies in a horribly understaffed offense, his performance hardly qualified as a crime against humanity. Clausen did not offer a great Lewin Career Forecast projection coming out of Notre Dame, but would have conceivably rated highly in this upcoming draft had he been a 4 year starter with, say, a 63% completion percentage.

Suffice it to say, Clausen may have been better off playing in a new system at Notre Dame to show his versatility than leaving for the NFL draft when he did. The team he plays for now has the first overall pick and is at least considering drafting a quarterback who they believe in more than Clausen. I wanted to investigate the wisdom of such a decision. To spend the first overall pick on a quarterback — even one that the Panthers believe in — you would first want to accurately conclude that nothing can be had from Clausen in 2011.

I was able to quickly generate a list of Jimmy Clausen comparable quarterbacks using only Clausen’s stats from his rookie year. Turns out it was a pretty unique season. Only rookies and second year players (compared to third and fourth year players) have ever achieved the kind of poor season that Clausen had in 2010 while also limiting an interception rate to a reasonable league average. The way to describe the careers of the Clausen comparables is that they all went to improve their careers and enjoy some success with the exception of Akili Smith. Smith had the kind of year that Clausen did as a second year starter, so he can be thrown out. McNabb, Cunningham, and particularly Carr all make for more sensible comparisions.

Of all comparisons, Jack Trudeau is by far the best for Clausen. The 1986 second round pick out of Illinois struggled to the tune of an 0-11 record as a rookie on a terrible team. The next year, the Colts were able to add Eric Dickerson, Trudeau settled in as an above average NFL quarterback for the next four seasons, leading the Colts to the playoffs in just his second year of 1987. Trudeau did not last in the NFL as a long term starting quarterback like McNabb or Cunningham did, nor did he get the opportunities that David Carr did to succeed. But Trudeau proves that it would not be unprecedented for the Panthers to get to 9 wins under Clausen next year by adding an offensive difference maker to pair with Steve Smith.

David Carr never did get the Texans to the playoffs, but as recently as 2006, it was thought that the Texans at least had the quarterback position filled. Carr never materialized as the Texans franchise quarterback for the same reason that Clausen couldn’t win in 2010: indecision with the ball led to too many sacks. Carr had a solidly above average season as a third year player in 2004, and improved greatly as a player in 2003. Truth is, if Jimmy Clausen ends up being either Jack Trudeau or David Carr, it would be hard to fault the Panthers for drafting Blaine Gabbert or Cam Newton in this draft.

However, a cursory look at the careers of Donovan McNabb and Randall Cunningham shows exactly why its too early to give up on Jimmy Clausen as a pro player. In each player’s first season as a starter, they lost more games than they won while posting rate stats near the bottom of the NFL. Each of the next two seasons, both McNabb and Cunningham threw 20 TDs for the Eagles as 24 and 25 year old players. If the belief is that Clausen can approach the 20 TD mark in 2011, the Panthers can win a bunch of games with him and there’s absolutely no reason to draft Gabbert or Newton. The pick, instead, would be best spent on an offensive talent that can help Clausen reach those goals.

Perhaps the best sign that the Panthers are planning on giving up on Clausen is that they aren’t considering drafting either A.J. Green or Julio Jones in that no. 1 slot. A defensive player at no. 1 wouldn’t make a lot of sense in the context of developing Clausen. Clausen would still likely fail to lead the Panthers to the playoffs throwing to just an aging Steve Smith. A defensive player makes sense for the Panthers if Clausen is just holding the QB spot warm while the team rebuilds, but in that case, I would support drafting a quarterback now instead of waiting. History shows that Clausen should be good enough to lead the Panthers to the playoffs, but that not all of Clausen’s closest comparables were able to do that, and those who didn’t lead teams to the playoffs in their first three seasons didn’t do it later on.

The Panthers should either give Clausen some help and develop him as a pro prospect or replace him now with Blaine Gabbert. While there isn’t strong evidence that Gabbert will develop into a better player than Clausen, getting Gabbert now buys more time for the coaching staff, and if the Panthers like him enough, I think that looking at Clausen’s closest comps shows that it makes sense for the Panthers to go in a different direction, if they feel Clausen is the next coming of Jack Trudeau or David Carr.

FNQB: What is Really Causing Ryan Mallett’s Depressed Draft Stock

Tonight, LiveBall Sports takes a look at Arkansas QB Ryan Mallett, and why his draft stock would possibly be falling at a time when Cam Newton and Blaine Gabbert are cruising towards the top of the draft. Put it this way: if Newton and Gabbert are top five picks, what would be the reason that Ryan Mallett shouldn’t be in play to head to the Vikings at no. 12 overall.

Mallett is not a top ten value as a quarterback, but he’s got a somewhat decent chance to be the best QB in this class. While I can’t give anyone a strong reason to pick him over Blaine Gabbert, I can show you why they are similar. Here are three quarterbacks from this NFL draft class, and their college stats:

Player A: 292 passing attempts, 65.4% completion, 30 TDs (10.3%), 7 INTs (2.4%), 23 sacks (7.3%)

Player B: 955 passing attempts, 57.8% completion, 69 TDs (7.2%), 24 INTs (2.5%), 61 sacks (6.0%)

Player C: 933 passing attempts, 60.9% completion, 40 TDs (4.3%), 18 INT (1.9%), 43 sacks (4.4%)

Those are the three highest rated players in this upcoming draft, in order: Cam Newton (A), Ryan Mallett (B), Blaine Gabbert (C). My point is to show you that Newton is a very different player statistically from the other two (lots of completions and touchdowns, small sample size, higher sack rate). But Gabbert and Mallett are pretty much the same player as a passer. Gabbert is an athlete, while Mallett is a statue. Mallett is taller and uses the pocket better. Again, they are more similar then they are different. I would have Gabbert first, given the choice.

With Blaine Gabbert nearly certain to be drafted in the top ten picks, then, why is Mallett widely perceived as a second rounder? Sure, his true value may be closer to the top of the second round than the top ten, but we know all about how needs at the position are driving up the value of similar players. After Gabbert and Newton are gone, why not Mallett?

One possible explanation revolves around the depth of the class after the top two, namely, that Jake Locker, Colin Kaepernick, and Christian Ponder can challenge Ryan Mallett to be the next quarterback taken. For sure, Ponder’s stock appears to be on the rise. But this explanation is, at best, insufficient, and at worst, nonsensical. There are, by my count, nine different teams who are looking to come away with at least some QB help in this draft. Not all nine are going to try to address the need in the first two rounds, but this is because the supply of available quarterbacks draftable in the first two rounds comes up short of nine. Even for teams that believe in Dalton/Kaepernick/Locker, that’s — at most — seven players who will be drafted in the first two rounds.

That’s why Mallett’s stock should be heading in a forward direction. And it may be now. But that’s still a wide gap between where historical comparables of Mallett would be taken, and where Mallett is projected.

All Low Completion Percentage Quarterbacks

I am now taking a look at the fortunes of players with some of the problems that Mallett’s detractors cite. Mallett left his fifth year on the table to go pro before his birthdate became a liability to his draft stock. Historically, the average (since 2005) pro NFL prospect completes between 61.5% and 62% of his collegiate passes, though players who don’t exhaust their college eligibility tend to be a bit lower than that.

Mallett’s not really a “low” completion percentage player (Jake Locker: 54%, for example) at 57.8% for his career, but that’s nearly 4% below the average draft propsect. If we look at all players at least two percent below average in completion percentage and no less than six percent below average, we get the following list of comparables: